The Journey

Travelling West depicts the journey of my friend Hossein, as he travelled overland from his home town, Qazvin, in

Western Iran, to England, seeking asylum. He left at Iranian New Year, March

2006, and arrived at a service station on the M1 in June the same year. During the three months he travelled by

bus to a village close to the Iran –Turkey border. From there he went by truck

to another village where he joined the smuggler route to get over the border,

travelling through the mountain passes on horse-back to avoid check points.

From a village on the Turkish side, he travelled by lorry and on foot: the

lorry took the refugees by road but when a check point was in sight, they had

to walk, at night, over the mountains to reconnect with the road and another

truck on the other side of that check point. From the Turkish city of Van, he

took a bus to Istanbul, using forged identity papers in case he was questioned at

one of the fourteen checkpoints on the way from Eastern to Western Turkey. From

Istanbul he went by lorry, with another group, to Ezmir and from there by boat

to the Greek mainland and on to Athens. At every point of change, he was passed

on to a new trafficker, each one arranged by the one before. From Athens he

went by plane to Paris, Orly where he took the metro to Gare du Nord and took

the train to Calais. At Calais, in the queue for food, provided by kindly

French charity workers, he met an old friend. They made a sleeping

place in the cabin of an old crane until, one night, after numerous attempts, they

got on a lorry which took them to England, disgorging them all in the car park

of a service station on the M1.

Hunger and Danger

This is the simplified outline of the journey, the bare

bones, if you like. The full story includes constant and gnawing fear and

anxiety, not knowing who he would encounter next, what the trafficker would be

like, what his fellow travellers would be like, what the conditions of travel

were like: the boat, for example, was not seaworthy and they only just avoided

drowning. The traffickers varied, some intensely violent, others, kind souls, themselves trapped in a debt-bondage cycle to another, ‘more senior’ trafficker

– a debt-bondage avoided by Hossein himself only because he took a risk and

refused the financial demands of his trafficker-in-chief once in England. It

was a risk that paid off. At times

he didn’t eat or drink for a week at a time, often at the most arduous points.

In the mountains, for example, they had only berries and snow. Even when there

was food, it was only bread and tea. The hardest thing though, was the

powerlessness, not knowing until the last minute, if the next trafficker would

come and if he could do the next stage of the journey or if he would be stuck,

locked in a dingy room forever unable even to return to Iran.

Masoud

-->

What really colours the entire journey, however, are the

relationships between Hossein and the people with whom he was connected. His

task was to escort two people from Istanbul to London. These two were from a

wealthy Qazvin family. The Trafficker-in-Chief, Masoud, was their older brother

and Hossein’s former employer. Hossein idolised this man. ‘He was a like a

prophet, well educated and always polite. I was only seventeen, from a poor

family, and had little education. He taught me everything.’ Masoud’s business,

where Hossein was employed, had failed, partly because he was member of an

opposition group, the Mujahideen, and was endlessly obstructed by other traders

in the bazaar, who were government supporters, and also because he was issued

with bogus penalties and fines by government officials. By way of revenge,

Masoud become a small-time crook, deliberately defrauding the other traders of

considerable amounts of money, and eventually fled Iran, in 2000, to escape his

debtors. Masoud had left Hossein in Iran to face both the police and the wrath

of the other traders in the bazaar. In the police cell he was beaten and

threatened with torture. He could hear the sounds of other prisoners being

tortured. Some six years passed during which Hossein was unable to work legally

because of his former connections with Masoud. When Masoud eventually contacted

Hossein and asked him to escort his brother and neice to England, Hossein eagerly

accepted, hoping their friendship might be restored and trusting that Masoud

would acknowledge what he had suffered on his behalf and would, somehow, make

amends. The plan was to meet Masoud and his brother and niece in Istanbul.

Masoud would fly from England, the other two from Iran. They all had money and

passports and could do this legally. Hossein had to make his way overland,

alone, with no money, no passport and equipped with nothing but his wits and

hope. He was to meet them in Istanbul.

The Meeting

When he eventually arrived in Istanbul, hungry, terrified,

and with only the clothes he was wearing, his delight on meeting his old

employer, friend and mentor was overwhelming. ‘When I met Masoud in Istanbul,

we hugged for whole minute. He cooked me a meal. It was a feast.’ Then, later

the same evening, came an unexpected twist: ‘They laughed at my clothes. I

hadn’t been able to wash. I knew I didn’t smell good. Masoud bought me new

clothes and a tooth-brush. Then he demanded I pay him back, even the toothbrush

was listed on the bill. For the last six years I had endured beatings and

threats in Iran, then risked my life travelling over the mountains and dodging

military check points in Turkey. I did all this for him. In return, he

presented me with the bill for a toothbrush.’

There was nothing Hossein could do. He was dependent on

Masoud who would finance the rest of the journey and, even then, only on the

condition that he escort his two relatives.

The realisation that he had lost, not only any hope of

reparation and recognition for his loyalty, but also the man he loved most in

the world, more, even, than anyone in his family, hit him harder than any of

the dangers on the journey. His ‘prophet’ had been replaced by a dangerous

criminal and trafficker, a cynical operator bent only on extortion and profit. For

a young man, very much alone in the world, the emotional impact was, perhaps, a

greater threat to his life than the furious Aegean Sea that almost engulfed

them on the next stage of his journey. Though not technically alone at this

stage, he was, in some ways, more alone than ever. He had responsibility for

two, ‘incompetent and half-witted rich kids.’ He still had his wits but hope for

his friendship with Masoud had evaporated entirely. He understood that, far

from being a friend, he had sunk from employer, to servant to bonded-serf and,

at best, would end up in London in debt to Masoud who would, doubtless, try to

get him to become a trafficker too in order to pay off the debt.

Conclusion

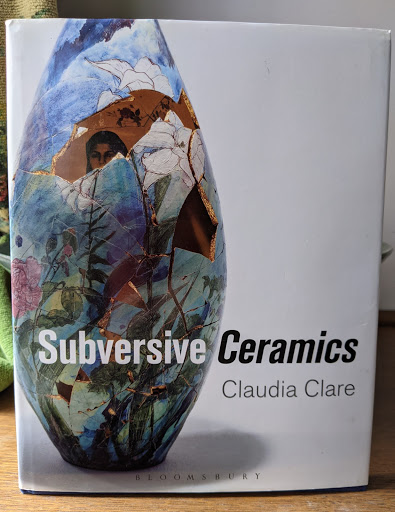

Travelling West shows the physical journey. It also depicts Hossein

making frequent phone calls. These punctuated every stage of the journey,

confirming its progress or not. They

also, gradually, settled the nature of the relationships between Hossein and

his family and between Hossein and Masoud. They indicate human connection but

they also signify immense loss.

Our traveller arrived at an anonymous motorway service

station in June 2006 alone, under threat of debt-bondage, and hungry. Since

then he has been slowly rebuilding his life, free of all contact with Masoud

and his family having refused to pay off any of the ‘debt.’ Journey’s end, for

this first stage of one man’s odyssey seeking asylum in Britain, was in Stoke

on Trent, where he was granted asylum in recognition of the political problems

that dogged him after Masoud left.

I am delighted to have the opportunity to show Travelling

West, for the first time, in the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, in Stoke on

Trent, as part of my display in the Award Show, 2013, at the British Ceramics

Biennial. This is a new work, made especially for the BCB. It is dedicated to

my friend, Hosssein, and to all refugees and migrant workers and their

extraordinary determination to succeed against the odds.